Almost half the nation’s children have experienced at least one or more types of serious childhood trauma, according to a new survey on adverse childhood experiences by the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). This translates into an estimated 34,825,978 children nationwide, say the researchers who analyzed the survey data.

Even more concerning, nearly a third of U.S. youth age 12-17 have experienced two or more types of childhood adversity that are likely to affect their physical and mental health as adults. Across the 50 U.S. states, the percentages range from 23 percent for New Jersey to 44.4 percent for Arizona.

The data are clear, says Dr. Christina Bethell: If more prevention, trauma-healing and resiliency training programs aren’t provided for children who have experienced trauma, and if our educational, juvenile

justice, mental health and medical systems are not changed to stop traumatizing already traumatized children, many of the nation’s children are likely to suffer chronic disease and mental illness. Not only will their lives be difficult, but the nation’s already high health care costs will soar even higher, she believes. Bethell is director of the National Maternal and Child Health Data Resource Center, part of the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). The Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Service Administration, sponsors the survey.

“We mapped the ACEs data in the survey as closely to the CDC’s ACE Study as possible,” said Bethell, who is also a professor of pediatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, and CAHMI’s director in the OHSU School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics.

The CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study), a ground-breaking epidemiological study that revealed a direct link between childhood trauma and the adult onset of chronic disease, mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence, measured ACEs in 17,000 adults in San Diego. The ACE study spawned similar ACE surveys in 18 states, which queried more thousands of adults about their childhoods. The Crittenton Foundation surveyed more than a thousand young adults and teens. But the NSCH was the first survey to measure current or recent trauma in such a large number of U.S. children.

Following is a visual journey through the data. Over the next few months, researchers will be extrapolating more information. Nearly 100,000 people are included in the National Survey of Children’s Health, which was first done in 2003/2004 to provide a baseline and broad range of information about children’s health. The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics conducts the survey, under the direction of the MCHB. CAHMI researchers analyze and interpret the data.

In the CDC’s ACE Study, the ten types of childhood adversity measured were:

physical, sexual, verbal abuse

physical and emotional neglect

a parent who’s an alcoholic (or addicted to other drugs) or diagnosed with a mental illness

witnessing a mother who experiences abuse

losing a parent to abandonment or divorce

a family member in jail

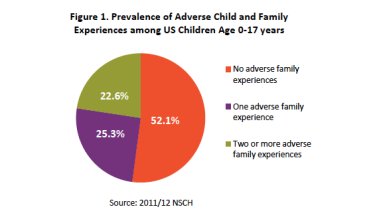

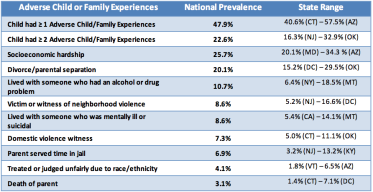

The National Survey of Children’s Health asked parents about nine types of adversity their children had or were currently living with. Nearly half of children, newborns to 17 years old — 47.9 percent — were reported to have at least one of the nine. About one-fifth — 22.6 percent — of children had two or more. (You can determine your ACE and resilience scores at Got Your ACE Score?)

Source: NSCH 2011/2012

“We were surprised at the rates of ACEs that we asked about,” says Bethell, “especially given that we know that any bias in the survey is in direction of under-reporting.” For example, it’s likely that many children are experiencing physical, sexual and verbal abuse; but it’s unlikely that parents would respond accurately to questions about those abuses if they are involved in the abuse.

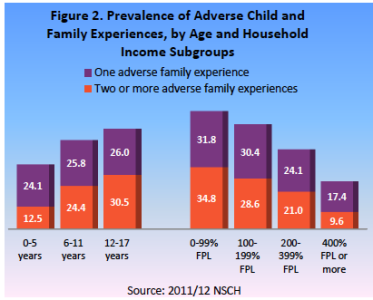

The survey results aren’t too surprising in that they show that childhood adversities increase as a child grows older, and decrease as family income rises. Nevertheless, ACEs are still experienced by more than one in three children under the age of six. Even in higher income families, more than one in four children have ACEs.

(FPL is an abbreviation for “federal poverty level” income. In the U.S., the current poverty level income for a family of four is $23,550. So, a 400% federal poverty level income for a family of four is $94,200. For more details, check out FamiliesUSA.org’s list of income levels by poverty level and family size.)

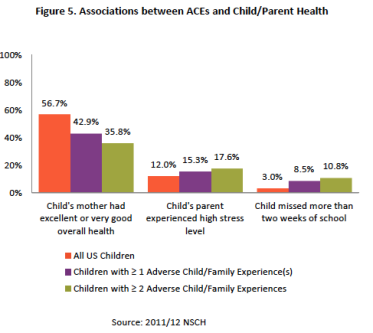

One of the interesting aspects of the survey is the interplay between childhood adversity and the health of parents and children. What’s not surprising is children with fewer ACEs have healthier mothers. And the higher a child’s ACE score, the increase in parent’s stress levels.

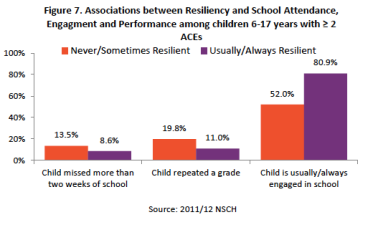

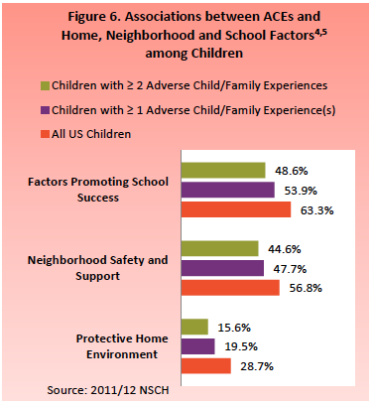

The survey’s data wasn’t all bad news. It also revealed how resilience can trump ACEs. Children aren’t born naturally resilient. The more that resilience is nurtured within them, and modeled and provided to them by their family and community, the more they are able to respond well to the stress they experience, which builds more resilience. Factors that build resilience in a child include living with a caring and healthy adult, having social connections, being involved in community activities, having family and friends who believe in a better future, and being taught how to calm themselves and to regulate their emotions, even at a very early age.

Though children who experienced ACEs had a harder time being calm and in control when faced with a challenge — which is one symptom of toxic stress and trauma — many were still able to do so. Yet, when children were less able to control themselves, they were more likely to miss school or to repeat a grade and less likely to be engaged in school activities.

Three of the measurements — witnessing or experiencing violence outside the home, socioeconomic hardship and experiencing racism or discrimination — address how a child’s environment affects their ACEs.

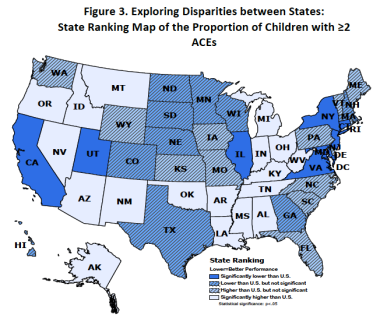

And, finally, the map below shows how childhood adversity varies among the states. Only nine states — California, Utah, Illinois, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware and New York — have childhood trauma rates significantly lower than the U.S. average.

Source: 2011/2012 NSCH

The significance of this survey may be profound, noted Bethell. If the ACE Study is to be believed — and so far, no research has challenged its findings — then a high proportion of children are already at risk for chronic disease and mental illness, she notes.

“We don’t know how this will play out for children,” says Bethell, “but if we take the data in the ACE Study and apply it, we would find ourselves with a pretty strong public health burden that, if we address it now, might be attenuated.

“Luckily, evidence is building for effective methods to build resilience, identify and heal trauma early, and improve a child’s social and emotional development, regardless of ACES. Of course, all efforts to prevent ACES remain central to public health in the U.S.”